You are here

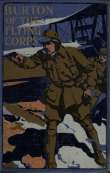

قراءة كتاب Burton of the Flying Corps

تنويه: تعرض هنا نبذة من اول ١٠ صفحات فقط من الكتاب الالكتروني، لقراءة الكتاب كاملا اضغط على الزر “اشتر الآن"

without exploding. Look here!"

He put a small quantity into a zinc pan, lit a match, and applied it. A column of suffocating smoke rose swiftly to the roof. Burton spluttered.

"Beautiful!" he gasped ironically. "I'm glad, old man; your fortune's made now, I suppose. But I can't say I like the stink. Takes your appetite away, don't it?"

"Ah! You mentioned lunch. Just get me that stuff like a good fellow; then I'll prepare my solution; and then we'll have lunch and you can dispose of me as you please."

II

Burton returned to the creek, boarded his flying-boat, and was soon skimming across country on the fifteen-mile flight to Chatham.

He had been Micklewright's fag at school, and the two had remained close friends ever since. Micklewright, after carrying all before him at Cambridge, devoted himself to research, and particularly to the study of explosives. To avoid the risk of shattering a neighbourhood, he had built his laboratory on the Luddenham Marshes, putting up the picturesque little cottage close at hand for his residence. There he lived attended only by an old woman, who often assured him that no one else would be content to stay in so dreary a spot. He had wished Burton, when he left school, to join him as assistant: but the younger fellow had no love for "stinks," and threw in his lot with a firm of aeroplane builders. Their factory being on the Isle of Sheppey, within a few miles of Micklewright's laboratory, the two friends saw each other pretty frequently; and when Burton started a flying-boat of his own, he often invited himself to spend a week-end with Micklewright, and took him for long flights for the good of his health, as he said: "an antidote to your poisonous stenches, old man."

Burton was so much accustomed to voyage in the air that he had ceased to pay much attention to the ordinary scenes on the earth beneath him. But he had completed nearly a third of his course when his eye was momentarily arrested by the sight of two motor-cycles, rapidly crossing the railway bridge at Snipeshill. To one of them was attached a side car, apparently occupied. Motor-cycles were frequently to be seen along the Canterbury road, but Burton was struck with a passing wonder that these cyclists had quitted the highway, and were careering along a road that led to no place of either interest or importance. If they were exploring they would soon realise that they had wasted their time, for the by-road rejoined the main road a few miles further east.

On arriving at Chatham, Burton did not descend near the cemetery, as he might have done with his landing chassis, but passed over the town and alighted in the Medway opposite the "Sun" pier. Thence he made his way to the address in the High Street given him by Micklewright. He was annoyed when he found the place closed.

"Just like old Pickles!" he thought. "He forgot it's Saturday." But, loth to have made his journey for nothing, he inquired for the private residence of the proprietor of the store, and luckily finding him at home, made known the object of his visit.

"I'm sorry I shall have to ask you to wait, sir," said the man. "The place is locked up, as you saw; my men have gone home, and I've an engagement that will keep me for an hour or so; perhaps I could send it over--some time this evening?"

"No, I'd better wait. Dr. Micklewright wants the stuff as soon as possible. When will it be ready?"

"If you'll be at the store at three o'clock I will have it ready packed."

It was now nearly two.

"No time to fly back to lunch and come again," thought Burton, as he departed. "I'll get something to eat at the 'Sun,' and ring old Pickles up and explain."

He made his way to the hotel, a little annoyed at wasting so fine an afternoon. Entering the telephone box he gave Micklewright's number and waited. Presently a girl's voice said--

"There's no reply. Shall I ring you off?"

"Oh! Try again, will you, please?"

Micklewright often took off the receiver in the laboratory, to avoid interruption during his experiments, and Burton supposed that such was the case now. He waited; a minute or two passed; then the girl's voice again--

"I can't put you on. There's something wrong with the line."

"Thank you very much," said Burton; he was always specially polite to the anonymous girls of the telephone exchange, because "they always sound so worried, poor things," as he said. "Bad luck all the time," he thought, as he hung up the receiver.

He passed to the coffee-room, ate a light lunch, smoked a cigarette, looked in at the billiard-room, and on the stroke of three reappeared at the chemist's store. In a few minutes he was provided with a package carefully wrapped, and by twenty minutes after the hour was soaring back to his friend's laboratory.

Alighting as before at the creek, he walked up the path. The door of the shed was locked. He rapped on it, but received no answer, and supposed that Micklewright had returned to the house, though he noticed with some surprise that his suit-case still stood where he had left it. He lifted it, went on to the cottage, and turned the handle of the front door. This also was locked. Feeling slightly irritated, Burton knocked more loudly. No one came to the door; there was not a sound from within. He knocked again; still without result. Leaving his suit-case on the doorstep, he went to the back, and tried the door on that side. It was locked.

"This is too bad," he thought. "Pickles is an absent-minded old buffer, but I never knew him so absolutely forgetful as this. Evidently he and the old woman are both out."

He returned to the front of the house, and seeing that the catch of one of the windows was not fastened, he threw up the lower sash, hoisted his suit-case over the sill, and himself dropped into the room. The table was laid for lunch, but nothing had been used.

"Rummy go!" said Burton to himself.

Conscious of a smell of burning, he crossed the passage, and glanced in at Micklewright's den, then at the kitchen, where the air was full of the fumes of something scorching. A saucepan stood on the dying fire. Lifting the lid, he saw that it contained browned and blackened potatoes. He opened the oven door, and fell back before a cloud of smoke impregnated with the odour of burnt flesh.

"They must have been called away very suddenly," he thought. "Perhaps there's a telegram that explains it."

He was returning to his friend's room when he was suddenly arrested by a slight sound within the house.

"Who's there?" he called, going to the door.

From the upper floor came an indescribable sound. Now seriously alarmed, Burton sprang up the stairs and entered Micklewright's bedroom. It was empty and undisturbed. The spare room which he was himself to occupy was equally unremarkable. Once more he heard the sound: it came from the housekeeper's room.

"Are you there?" he called, listening at the closed door.

He flung it open at a repetition of the inarticulate sound.